Civil War in Sudan: Struggle for Power, Gold, and Control

Long before civil war in Sudan started, one morning when the streets of Khartoum filled with people. Women waved their scarves, and young men raised Sudanese flags, chanting, “Freedom, Peace, and Justice.” After three decades under Omar al-Bashir’s dictatorship, the people of Sudan rose with unprecedented strength. The protests grew so massive that even the army had to bow to public pressure. On April 11, 2019, Omar al-Bashir’s rule came to an end. People believed Sudan’s days were about to change. But the light of revolution soon dimmed.

After Bashir’s removal, a transitional government was formed a fragile partnership between the military and civilian representatives. The army was led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and alongside him stood another powerful figure, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo.

Profile of General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti)

General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known to everyone as Hemedti, the commander of a paramilitary force called the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). His story, like Sudan’s history itself, is complex. Critics see him as brutal and ruthless during civil war in Sudan, while supporters view him as courageous, the man who helped end Bashir’s infamous regime.

Hemedti came from humble beginnings, a branch of a camel-herding tribe in Darfur. After quitting school at a young age, he made a living trading camels. His business skills and opportunism turned him into a powerful local warlord the head of a militia, a business empire, and a political machine.

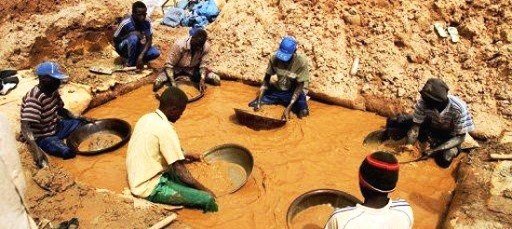

By seizing control of Darfur’s largest gold mine, he expanded his influence and became Sudan’s most prominent gold exporter. In 2013, Omar al-Bashir officially appointed Hemedti as the RSF’s commander, supplying him with modern weapons, uniforms, and military support.

Foreign Involvement in the Civil War in Sudan

The mining industry of Sudan is mostly driven by gold mining . During civil war in Sudan, the UAE plays a quiet but powerful role. Sudanese gold has flowed into Dubai for years. According to a Reuter’s report, gold worth tens of billions was illegally exported to the UAE each year. Little of that reached Sudan’s treasury, most was divided among militia networks. The RSF used this money to buy more weapons.

The UAE officially denies involvement in conflict in Sudan, but experts say its silent backing is the RSF’s lifeline. Egypt supports Sudan’s army, wanting a strong ally on its southern border. Russia, pursuing its own interests, seeks a naval base on the Red Sea and alternates its support between the army and RSF as needed. The U.S. and Western nations watch closely but avoid openly backing either side.

By 2015, when Saudi Arabia and the UAE asked Sudan to send troops to Yemen, Hemedti seized the opportunity, sending RSF fighters as mercenaries. This strengthened his ties with the UAE and even connected him directly to Abu Dhabi’s royal family.

He also partnered with Russia’s private military company, Wagner Group, gaining both combat training and commercial benefits through the gold trade. RSF recruited young Sudanese and men from neighboring countries, offering high pay to join.

Through a mix of modern weaponry, business acumen, and foreign backing, Hemedti built enormous political and economic power.

His brother, Abdul Rahim Dagalo, organized a network for smuggling gold abroad from Darfur to Khartoum, across Chad and the Central African Republic, and finally to Dubai. Once refined in the UAE’s markets, Sudanese gold was sold internationally.

It carried no “Made in Sudan” label but its shine reflected the rubble of Darfur, its burning villages, and its fleeing children. With this wealth, the RSF became a state within a state.

It bought modern weapons, paid its fighters high salaries, and spread its influence nationwide. Meanwhile, Sudan’s regular army began to feel threatened fearing the RSF might one day challenge its authority. This fear eventually turned into war between Sudan’s rival factions.

Battles for Khartoum and Division of Control

After Bashir’s fall, both forces remained part of the transitional government, but mistrust lingered. The army wanted to integrate the RSF into a single national command. Hemedti refused, insisting his force remain autonomous to “protect the nation.”

The dispute dragged on, until April 2023, when open armed conflict erupted. Gunfire echoed across Khartoum. Tanks rolled through the streets. In the early days of civil war in Sudan, the RSF gained rapid success seizing the presidential palace, army headquarters, and the airport. They captured the northern and western parts of the capital, while the army held the east Bahri and Omdurman.

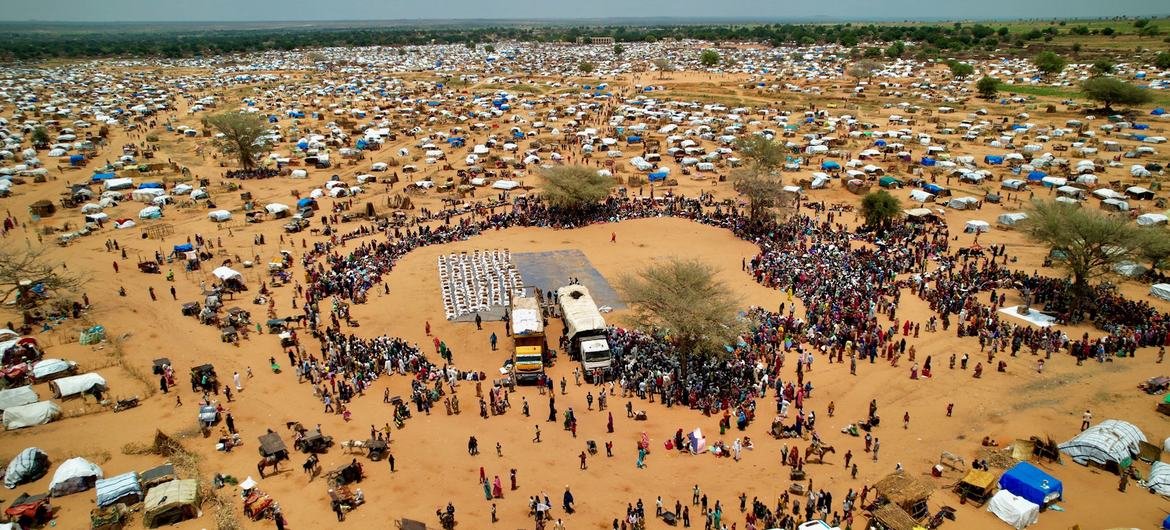

The Nile’s banks ran red with blood. Within weeks, the war spread to Darfur. RSF gained control of major cities like Al-Fashir, Nyala, and Al-Geneina. In Al-Geneina, the devastation was so great that the UN called it “ethnic cleansing.” Thousands were killed; villages were burned to the ground. Today, most of western Darfur remains under Hemedti’s control.

During Sudanese civil conflict, General al-Burhan moved his headquarters to the coastal city of Port Sudan the new seat of the official government. Northern and eastern Sudan, as well as the Red Sea coast, remain under army control, while central Kordofan is contested territory.

Thus, Sudan’s map is now split in two, the east and north with the army, the west and capital mostly with the RSF. This division has ignited a new battle for control over the nation’s resources: RSF holds the gold mines, the army controls the ports and trade routes. This fragile balance keeps the war alive.

Global Response and UN’s Role in the Civil War in Sudan

While the world’s attention was fixed on the Gaza war a few weeks ago, the suffering of the Palestinian people sparked global outrage and protests. However, parallel to this, another devastating conflict was unfolding in Sudan a brutal war for control between two rival factions.

The killings of innocent Sudanese civilians during conflict in Sudan went largely unnoticed by the international community until the ceasefire in Gaza shifted the global focus. Now, the world is beginning to recognize the terror and destruction unleashed by powerful warlords in Sudan.

Estimates suggest that thousands have been killed in this struggle for dominance. The people of Sudan are desperately waiting for international help and intervention to stop the war and restore peace and stability in their country.

Caught in the middle are Sudan’s people. The UN says due to war between Sudan’s rival factions more than 10 million have been displaced within the country and over 2 million have fled abroad to Chad, Egypt, and South Sudan. Food shortages, lack of water, and disease have deepened the crisis. Khartoum, once the heart of Sudan, is now a symbol of ruin. Buildings along the Nile lie in rubble. On some surviving walls, the 2019 slogans, “Freedom, Peace, Justice” are still visible, scarred by bullet holes.

Conclusion: A Nation Divided by Gold and Power

Civil War in Sudan is no longer just a war for power, it is a war over gold, the source of all wealth and blood in Sudan. From the same soil where Sudanese women once mined gold for jewellery, that gold is now melted into bullets. Behind every bar of gold lies a story of blood. Every shining brick hides a worker’s death and a village’s grief. For Hemedti, gold is power.

For the army, it is the threat that slipped from their control. This gold has poisoned Sudan’s politics, from foreign investors to local warlords, everyone is chasing it. Sudan is now a land of two states, two armies, and two realities: the RSF, drenched in gold and guns, and the army, paralyzed by its own ambitions. Between them stands the people, those who once dreamed of revolution but now search for life among ruins.

Even if peace someday returns, Sudan’s wounds may take decades to heal. Because it wasn’t just buildings that fell, it was dreams. That bright morning in 2019, when young Sudanese chanted for freedom, is now only a memory. Perhaps someday, songs will again echo along the Nile’s banks but only when Sudan’s rulers see gold not as private wealth, but as the people’s trust.

Thanking your reading the article. If you like it article, you may like this as well:

It’s concerning to hear about the struggle for power and resources mentioned in the article; I found some additional context on https://tinyfun.io/game/wings-of-fire-merge that helped me understand the historical complexities a bit better.